On the occasion of the 92nd birth anniversary of one of American cinema’s greatest auteurs, Stanley Kubrick, let’s revisit his formidable body of work from a fresh perspective for a new generation of cinephiles. Universally acclaimed for his meticulousness and his endless craving for innovation, Kubrick had succeeded winning over the masses and critics alike for well over four decades through the means of his thought-provoking, genre-transcending works of cinematic art.

Read A Love Letter To The Grandmaster Of Cinema

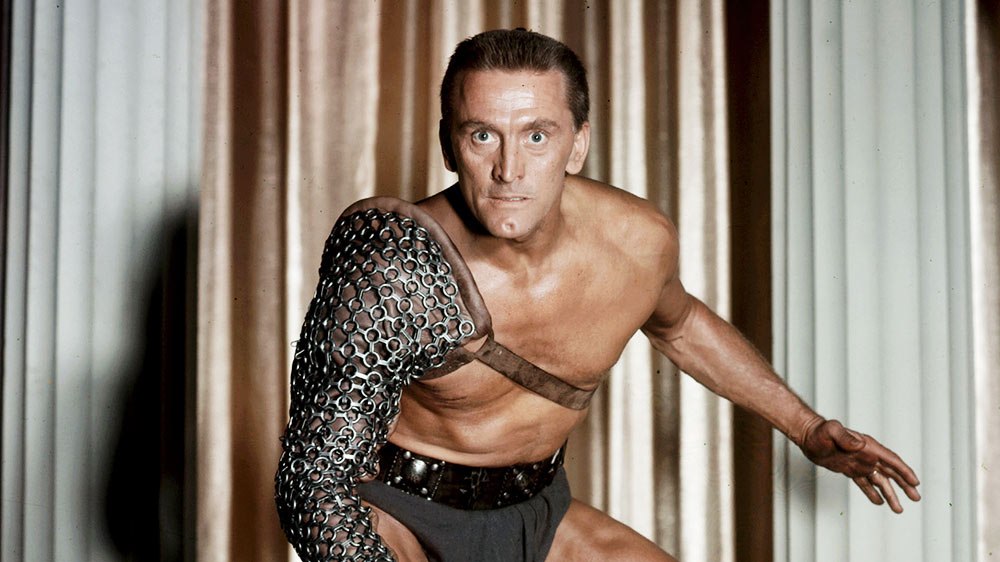

His celebrated oeuvre seems to cover the entire movie horizon. A testament to his versatility as a filmmaker, it contains timeless gems like The Killing (1956)—a film noir masterpiece; Paths of Glory (1957)—an anti-war classic; Spartacus (1960)—an epic drama; 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)—a sci-fi extravaganza; A Clockwork Orange (1971)—a futuristic crime thriller; Barry Lyndon (1975)—a sprawling period drama; The Shining (1980)—an atmospheric psychological horror masterpiece; Eyes Wide Shut (1999)—a psychedelic suspense thriller.

Interestingly, Kubrick’s debut feature, Fear and Desire, which released in 1953, has mostly remained in obscurity. He made the film at the age of 24. It deals with the theme of war, which he explored in many of his films, including Full Metal Jacket (1987) and the war comedy Dr. Strangelove (1964). Apparently, Kubrick wasn’t too pleased with Fear and Desire and so in order to prevent people from seeing it or distributing it, he had burned the negative. Yet the film somehow survived and is now available online in its restored form. It serves as a solid forerunner to the masterful films that followed it.

Watch Fear and Desire here

Amongst his towering contemporaries, Kubrick was arguably the most consummate filmmaker—an undisputed master of all trades. While most of his contemporaries tried to focus on a genre in particular, Kubrick continued to tread the hitherto uncharted territories, which catapulted him into a very elite league of filmmakers. Following a successful early stint in Hollywood, Kubrick entered a very difficult phase in his life—during which he suffered both personally as well as professionally—that culminated in his second divorce. Disillusioned with the razzmatazz of Hollywood, Kubrick shifted his base to England in the 1960s, never to return again.

In was in the UK that Kubrick would make his most influential movies: right from Lolita (1962) to Eyes Wide Shut (1999). The beauty of a quintessential Kubrick film is that it forces the viewers to think, for the end product is always more than the sum of its parts. Let’s consider his 1975 period drama Barry Lyndon, starring Ryan O’Neal in the titular role. Based on a novel by William Makepeace Thackeray, the film belongs to the highest echelons of cinema. Kubrick had an eye for spotting literary works which had the potential to be made into formidable films. This is arguably the greatest period drama films ever made.

Barry Lyndon serves as a masterclass on set lighting, cinematography, and cinematic storytelling. Ever frame of the film is reminiscent of 18th century paintings. There are such breathtaking scenes in the film which are exposed using candle lights alone thanks to a lens developed for NASA to take pictures of the dark side of the Moon. Kubrick deliberately keeps his characters at a distance as he doesn’t want the viewers to feel empathy for his characters. And the narration serves as a conduit, like a wand in the hands of the wizard who uses it to unleash his immaculate design. None of the characters are likable and this only adds to the above effect. Perhaps, only Kubrick could have achieved it with such aplomb. Not a moment goes by when he is not in command.

The great American film critic Roger Ebert sums it up perfectly: “The film has the arrogance of genius. Never mind its budget or the perfectionism in its 300-day shooting schedule. How many directors would have had Kubrick’s confidence in taking this ultimately inconsequential story of a man’s rise and fall, and realizing it in a style that dictates our attitude toward it? We don’t simply see Kubrick’s movie, we see it in the frame of mind he insists on — unless we’re so closed to the notion of directorial styles that the whole thing just seems like a beautiful extravagance (which it is). There is no other way to see Barry than the way Kubrick sees him.”

Watch this video essay to understand how Kubrick shot Barry Lyndon

Kubrick’s Paths of Glory mocks the draconian, jingoistic practices preached and promoted in the armed forces in the name of patriotism. Kubrick limns a grim picture of moral decline in a diabolical world that men have designed for themselves where human life is valued in terms of squares of yards of land captured from the clutches of their adversaries. The Paths of Glory also underlines the corruptibility of power and its infinite sphere of influence that encompasses anyone and everyone. The French auteur and critic François Truffaut had once famously said that it was impossible to make an anti-war movie, for the action would argue in favor of itself. Kubrick by making Paths of Glory proved him wrong, once and for all.

The futility of war is best demonstrated by the film’s unforgettable final sequence wherein the French soldiers of the 701st regiment are seen enjoying the performance of a captured German lady (portrayed by Christiane Susanne Harlan, Kubrick’s future wife) who, after being ridiculed and humiliated by the presenter, is forcibly asked to sing a song for the entertainment of the French soldiers. The lady, despite being in a state of shock, sings the German folk song “The Faithful Hussar”. The seemingly indifferent soldiers are suddenly moved by the poignancy of the song and her mellifluous voice as they start to sing it in unison with her as tears start to drip from their eyes.

Watch the poignant song here

Kubrick’s magnum opus 2001: A Space Odyssey best demonstrates his mastery over the use of cinematic space through long uncut shots. he film is Kubrick’s tribute to the endless uncertainties of the universe. Ebert eloquently comments upon what Kubrick achieves with the film, “The genius is not in how much he does in ‘2001: A Space Odyssey,’ but in how little. This is the work of an artist so sublimely confident that he doesn’t include a single shot simply to keep our attention. He reduces each scene to its essence, and leaves it on screen long enough for us to contemplate it, to inhabit it in our imaginations.”

Watch “Standing on the Shoulders of Kubrick” Mini Documentary

Such was the level of meticulousness involved that Kubrick actually two hired NASA scientists—Fred Ordway as the science advisor and Harry Lange as the production designer—to lead the movie’s modeling team. Lange’s 2-D sketches were transformed into actual models by Anthony Masters. The film played an instrumental role in reinventing the Sci-Fi genre in the world of cinema. The groundbreaking technological advancements—including the unprecedented use of Front projection, employed through the means of Retroreflectors and Mattes, in cinema—unleashed in the film paved the way for a whole new type of cinema that began to rely heavily on special effects, thereby paying the way for the future of filmmaking.

Sadly, Kubrick passed away in the year 1999, just a year before the world would enter the century he made famous through his magnum opus. His final film, Eyes Wide Shut, was released posthumously. It revolves around a New York based doctor (essayed by Tom Cruise) who gets perplexed when his wife reveals a painful secret to him. Consequently, he embarks on a harrowing, night-long odyssey of sexual and moral discovery. The film was wrongly marketed as an erotic thriller and as a result it failed to attract the right set of audiences at the time of its release. However, it has significantly grown in stature in the recent years. Also, it’s worth mentioning here that Kubrick’s unfulfilled dream project A.I. Artificial Intelligence was finally realized by his good friend and fellow American filmmaker Steven Spielberg in the year 2001. Spielberg dedicated the film to the memory of Kubrick.